Affiliate Marketing

Performance-based marketing which rewards affiliates for each customer brought by the affiliate's marketing efforts.

B2B Marketing

Business-to-business marketing refers to the marketing of products or services to other businesses and organizations.

Branding

The process of researching, developing, and applying a distinctive feature or set of features to your organization so that consumers associate your brand with your products or services.

eCommerce

Ecommerce, or electronic commerce, refers to transactions conducted via the internet. Every time individuals and companies are buying or selling products and services online they’re engaging in ecommerce.

Influencer Marketing

Influencer marketing is a type of social media marketing that uses endorsements and product mentions from influencers–individuals who have a dedicated social following and are viewed as experts within their niche.

LinkedIn Marketing

LinkedIn offers a lot of opportunities and is the ideal resource for B2B marketing. But without the right knowledge, it becomes just another time-sucking social network. Next time you're on LinkedIn, spend at least thirty minutes doing some advanced searches or group searches, and see if you don't come up with at least five prospects.

Marketing Automation

Marketing automation is technology that manages marketing processes and multifunctional campaigns, across multiple channels, automatically. With marketing automation, businesses can target customers with automated messages across email, web, social, and text. Messages are sent automatically, according to sets of instructions called workflows.

Non-Profit Marketing

Nonprofit marketing is the use of marketing tactics by a nonprofit organization. Marketing goals may include promoting the organization and its message, raising funds, encouraging membership, engaging volunteers, and driving political or social change

PR Marketing

A public relations (PR) strategy may play a key role in an organization's promotional strategy. A planned approach to leveraging public relations opportunities can be just as important as advertising and sales promotions. Public relations is one of the most effective methods to communicate and relate to the market.

Twitter Marketing

With more than 145 million active daily users, Twitter should be a part of your marketing strategy. It's the fifth most popular social media network, and it'sis a gold mine of customer insights and opportunities to build your brand, drive sales and win fans.

Advertising

Marketing communication that employs an openly sponsored, non-personal message to promote or sell a product, service or idea.

B2C Marketing

Business-to-customer marketing refers to the tactics and strategies a company uses to promote its products and services to individual people.

Content Marketing

Content marketing is a form of marketing focused on creating, publishing, and distributing content for a targeted audience online.

Email Marketing

Email marketing it involves using email to send advertisements, request business, or solicit sales or donations.

Instagram Marketing

With an advertising audience of more than 1.16 billion people, Instagram offers dramatic reach for brands. And the potential reach of Instagram marketing has grown substantially this year—increasing by 76 million people in just the last quarter.

Local Marketing

Local marketing—also referred to as local store marketing or neighborhood marketing—specifically targets the community around a physical store or restaurant. Promotional messages are directed to the local population, rather than the mass market

Mobile Marketing

Mobile marketing is a multi-channel, digital marketing strategy aimed at reaching a target audience on their smartphones, tablets, and/or other mobile devices, via websites, email, SMS and MMS, social media, and apps.

Neuro Marketing

Neuromarketing Meaning: Essentially, neuromarketing is designing your content, website, etc. to ellicit particular neurological reactions that are associated with buying or emotions linked to buying. Using neuromarketing, you can rethink your strategies and create smarter marketing that will boost the effectiveness of your efforts.

Pinterest Marketing

Pinterest is a goldmine when it comes to marketing. But finding success with your Pinterest marketing strategy goes beyond just having a great profile image and company description for your Pinterest business account. Making Pinterest marketing work boils down to having a clear strategy that resonates with your business goals.

Sales

Sales are activities related to selling or the number of goods sold in a given targeted time period. The delivery of a service for a cost is also considered a sale. The seller, or the provider of the goods or services, completes a sale in response to an acquisition, appropriation, requisition, or a direct interaction with the buyer at the point of sale

YouTube Marketing

YouTube marketing is often overlooked by social media marketers. Some think YouTube counts as a social media network. Others see it as more of an online video platform. Either way, there are countless marketing opportunities on YouTube—especially if your audience is on the platform and your competitors aren't.

Adwords Marketing

Google AdWords' system is where advertisers pay to display brief advertisements based on cookies and keywords.

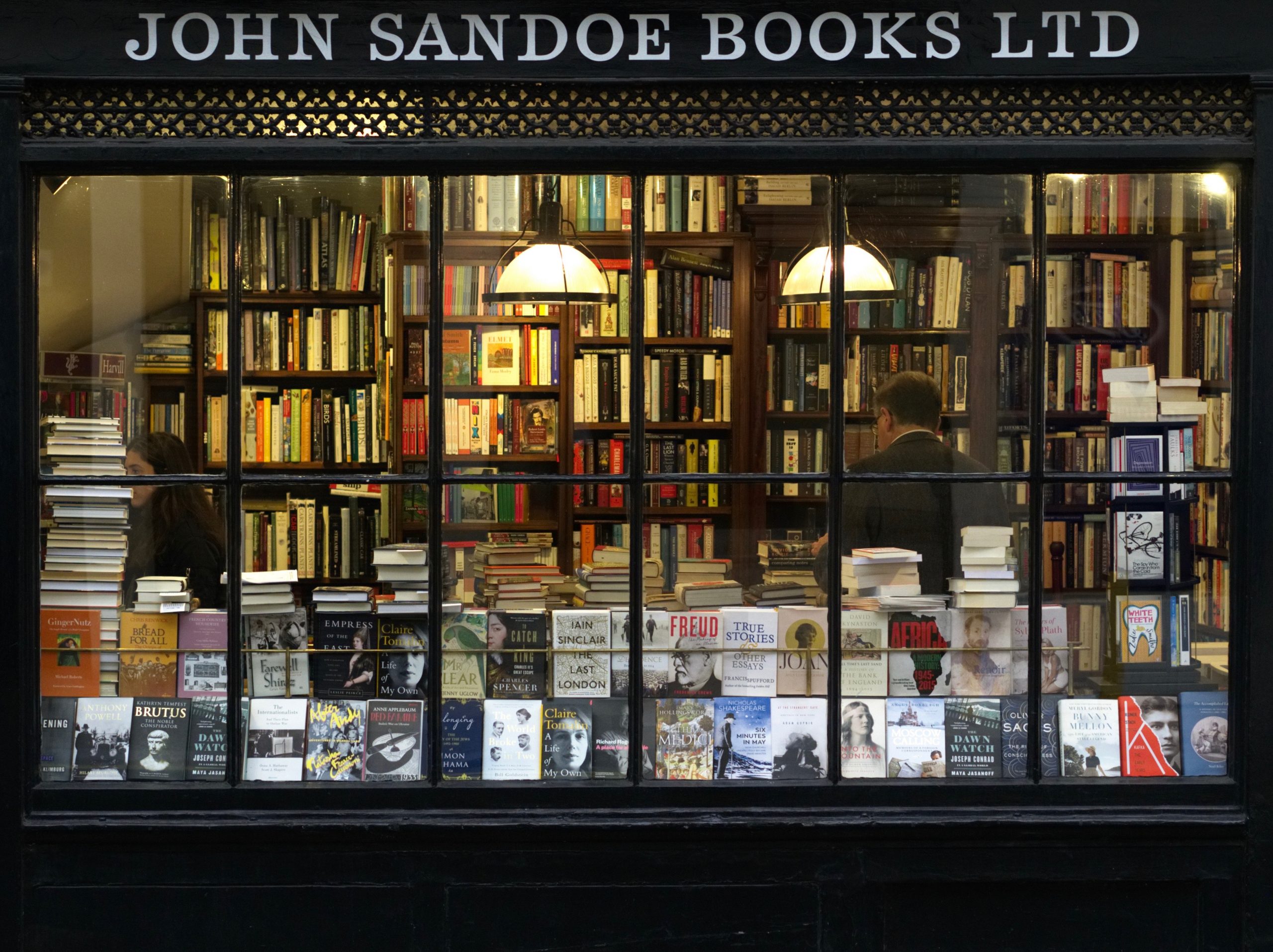

Book Marketing

By following in the footsteps of those who have succeeded before you, you can create a focused and effective book marketing plan that will get people snatching up your masterpiece.

CRM Marketing

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and Marketing CRM leverages and amplifies customer base of an organization through efficacious and efficient marketing.

Facebook Marketing

Refers to creating and actively using a Facebook page or Group as a communications channel to maintain contact with and attract customers.

Internet Marketing

Online marketing, also known as internet marketing or web advertising, is a form of marketing that uses the internet to deliver promotional messages to customers through digital channels such as search engines, email, websites, and social media.

Market Research

Email marketing it involves using email to send advertisements, request business, or solicit sales or donations.

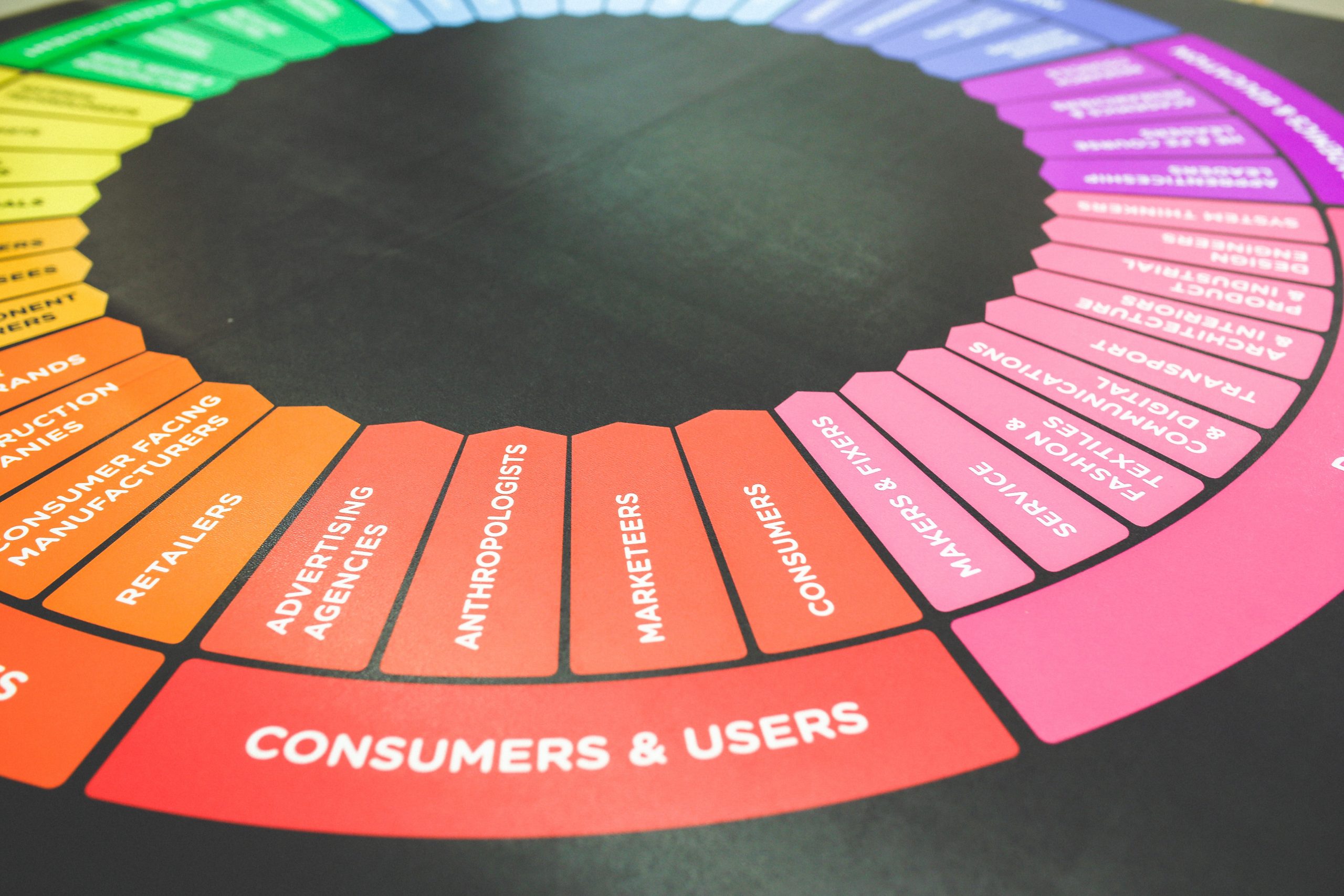

Marketing

Marketing refers to activities a company undertakes to promote the buying or selling of a product, service, or good. In 2017, The New York Times described it as "the art of telling stories so enthralling that people lose track of their wallets".

Network Marketing

Multi-level marketing, also called network marketing or pyramid selling, is a controversial marketing strategy for the sale of products or services where the revenue of the MLM company is derived from a non-salaried workforce selling the company's products or services.

PPC Marketing

PPC stands for pay-per-click, a model of internet marketing in which advertisers pay a fee each time one of their ads is clicked. Essentially, it's a way of buying visits to your site, rather than attempting to "earn" those visits organically. Search engine advertising is one of the most popular forms of PPC.

Social Marketing

Small Business Marketing Marketing is meant to raise brand awareness and build a pipeline of qualified leads that turn into sales. With a small business, getting the word out can be challenging due to less visibility and lack of resources (like budget or time).

Small Business

Email marketing it involves using email to send advertisements, request business, or solicit sales or donations.

Video Marketing

Video marketing is using videos to promote and market your product or service, increase engagement on your digital and social channels, educate your consumers and customers, and reach your audience with a new medium.

Latest Posts

- GTM 90: The GTM Playbook Under Attack and Bootstrapping a Community to Multi-Million Dollar Revenue with James Kaikis

James Kaikis currently serves as the Head of Go-To-Market and Chief Solutions Officer at TestBox, an innovative company revolutionizing the way buyers interact with product demos. Before his tenure at TestBox, James co-founded the PreSales Collective with Yuji Higashi. Under their leadership, the community became a pivotal resource in the presales domain until its successful acquisition […]

Read More » - 7 Simple Steps to Boost a Prospect’s Mood and Improve Sales

A good salesperson knows that success starts with making connections, building rapport, and creating a positive space. Short and irritable prospects make it difficult to have any meaningful conversation and make your job much harder than it needs to be. Building rapport and making connections doesn’t have to take long, and it’s well worth the […]

Read More » - Why I Teach the Oldest Sales Approach and Call It Modern

Discover how timeless wisdom and trusted advisors shape successful leadership and sales strategies, transcending centuries.

Read More » - 100+ Motivational Quotes About Hard Work That’ll Help You Reach Your Goals

Success doesn’t come easy — even the most dedicated entrepreneur sometimes finds it tough to stay on track. It’s hard for businesses to keep their employees motivated all the time. I even find myself struggling with motivation on days when challenges feel insurmountable. When I’m experiencing a rut, I look for sources of inspiration. That’s […]

Read More » - 9 Sales Pitch Examples (Plus Tips on How to Write Your Own)

Your sales pitch can make or break the deal, so it’s a good idea to have that nailed down before meeting with your customer. It’s your opening line, your verbal business card, and the first thing your customer will hear when you call or meet with them. I’ve been in sales for almost 16 years […]

Read More » - WA’s King County Wants to Hire DC Advocate

Washington’s King County is looking for a federal government relations shop to help it stay abreast of policies and legislation that could impact its 2.2M people and cities such as Seattle, Bellevue and Redmond.

Read More » - Navigators Global Guides Japan

Navigators Global has signed a one-year contract to advise Japan’s embassy on legislation in Congress and White House policies and actions that could affect the US and Japan relationship.

Read More » - How Not To Chase Ambulances

There’s a fine line between newsjacking and taking advantage, aka ambulance chasing. Our job as PR professionals is to tread it carefully.

Read More » - FH Veteran Slatin Moves to Husch Blackwell

Husch Blackwell Strategies has added FleishmanHillard alum Michael Slatin as a principal in its public affairs group.

Read More »